CHICAGO — When I read the email again the other day, I realized it was classic Tuyet.

“Look at all the trouble you’ve gotten me into,” she’d written.

And that was really funny, because she never needed any help getting into the kind of trouble that came from calling out the powerful. It was also typical of her to downplay her own work and credit others — and to crack jokes about all of it.

She’d sent me the email in February 2011, less than two weeks before the city elections. As executive director of the nonprofit Asian American Institute, Tuyet Le had worked with allies to organize the first mayoral forum on issues affecting Asian Americans.

All of the top mayoral candidates committed to participating in the historic event — all of them except the frontrunner, former congressman and White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel.

Instead, Emanuel chose to attend a fundraiser hosted by a Korean American group. Its leaders told a community newspaper they thought Emanuel might help them secure government jobs.

When Tuyet shared the story with me, we both thought it sounded like an old-school Chicago patronage-for-votes deal, with a touch of divide-and-conquer.

Of course, when I called Emanuel’s campaign for comment, I got a loud earful informing me that their candidate would never, ever think to do anything that didn’t move Chicago forward.

Though Emanuel didn’t show up to the forum, 1,000 other people did — a pivotal display of unity and strength for the Asian American community.

Tuyet drew on that budding power when she issued a statement chastising Emanuel for skipping the event: “There are 60,000 Asian Americans registered in Chicago, and we can make the difference if Emanuel is trying to avoid a run-off.”

Her comment irked some Rahm fans within the Asian American community. One of them circulated a letter accusing Tuyet of misrepresenting and trying to “intimidate” the next mayor of Chicago.

“I have known Mr. Emanuel for 17 years and he loves Asian-Americans, just like he loves Whites, Hispanics and African-Americans,” the letter said.

Tuyet converted her annoyance into amusement.

“I’m glad to know that Rahm loves so many people,” she wrote me.

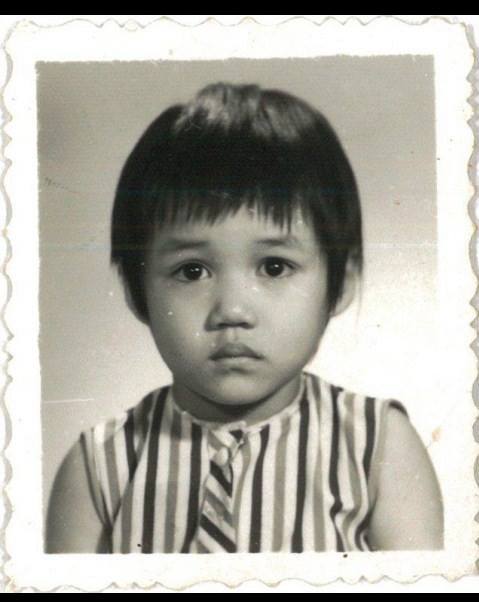

I’m laughing at this all over again, which is the best way I know to grieve and honor Tuyet. She died a couple of weeks ago at age 53. She had been fighting lung cancer for three years, though few of us knew about her illness until we got the news that she’d passed.

“I kept it a small circle because I’ve always been a very private person,” Tuyet explained in a goodbye email friends circulated after she died. “Growing up with a disability, I got a lot of attention for being sick. I didn’t want to relate to people in that way again. I’ve never known what to do with attention.”

Yet she was deserving of all the attention she got, and so much more.

Small of stature, unable to walk without a limp or a crutch, an immigrant who exemplified what it meant to be an American and a neighbor, Tuyet was a force who became one of the city’s most consequential community and civil rights leaders. Her work impacted countless people who don’t even know her name.

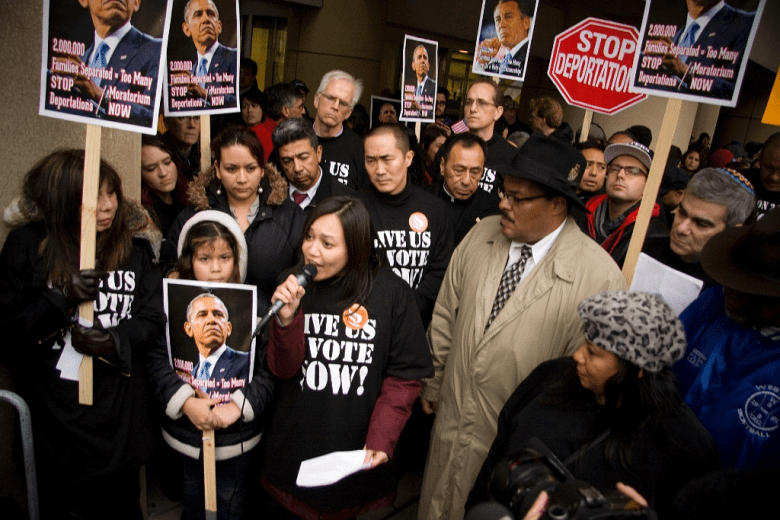

Tuyet led the Asian American Institute in its shift to become Asian Americans Advancing Justice Chicago, serving as executive director of the organization for more than 18 years. Its organizing built political power by bringing different regional, national and ethnic groups together, resulting in the creation of an annual Asian American Action Day at the state capitol and an Asian American caucus in the legislature.

“Folks probably don’t know that she is the reason there is a progressive Asian American political movement in Illinois,” said Nebula Li, one of her many proteges at Advancing Justice, who’s now a program officer for the Lawyers Trust Fund of Illinois, a nonprofit foundation.

Tuyet also assisted and protected others whose voices went unheard by those in power. She and her team helped strengthen the city’s sanctuary law and pass the state’s TRUST Act; both measures block local police from assisting in federal immigration enforcement. She was a longtime member of the boards for the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights and for Access Living, the area’s leading advocacy organization for disabled people.

At a time when many powerful Americans make a cruel sport of villainizing the most vulnerable, Tuyet stood out for spreading compassion, and for having a good time while doing it.

She also had a moving personal story that she was reluctant to share until she realized it could help others.

Born in Vietnam in 1972, she was the youngest of five kids of Kế Văn Lê and Liên Thị Mộng Nguyễn. As a child, Tuyet contracted polio, which led to scoliosis and, over the years, multiple surgeries and treatments, according to an obituary shared by her family.

In 1975, Saigon fell to North Vietnam. Like thousands of others, Tuyet’s family fled for safety. As she told the story later, one of her uncles secured a spot on a fishing boat by trading his navigation skills. He also insisted on including his seven siblings and their families, so 31 relatives crowded onto the boat along with hundreds of others trying to escape.

Even in her matter-of-fact account, Tuyet made it clear the boat was not seaworthy. “Several days later at sea, a Taiwanese ship pulled alongside with orders to rescue only Chinese refugees,” she said in a 2017 speech. That meant the ship would only take two of the people on the fishing boat.

But “the father and daughter refused their safe passage unless we could all go with them,” Tuyet recalled. The Taiwanese crew gave in and took women and children onto the ship, while the men stayed on the fishing boat. Both vessels eventually made it to the Philippines.

From there Tuyet’s family continued to the United States as refugees. A Lutheran church in Milwaukee “sponsored” the family with housing, English lessons and medical care. Tuyet’s father found work as a machinist while her mother cleaned hotel rooms.

“We were fortunate to come at a time when the U.S. refugee policies supported us,” Tuyet said. “Of course, we tried to make it on our own as soon as possible, but knowing you have a safety net gives you the courage to excel. This is the promise of America that immigrants flock towards. But this promise has been broken for too many.”

After high school, Tuyet went to Northwestern University, where we lived in the same dorm our freshman year. I got to know her — and so did everybody else in the building — because of her job as a door monitor: In the evening she sat at a table inside the front entrance and asked visitors to sign in.

It soon became a hangout spot. When she had a shift, anyone in need of a study break could go downstairs and find a gathering of people telling stories and cracking jokes, led by the door monitor herself. I remember hearing Tuyet’s laugh from way down the hall as I approached: a giggle that built into a rat-tat-tat, like a machine gun firing rounds of uncontrolled delight.

“It feels like you’re flapping your arms and you’re pretending to fly and you kind of lift off the ground and then settle back down,” as Li described it many years later.

As an upperclassman, Tuyet joined a campaign to convince Northwestern to launch an Asian American studies program. Two years after we graduated, a group of students went on a hunger strike to force the issue. NU finally created a program in 1996.

By then Tuyet and I had fallen out of touch. We reconnected a few years later through Chicago politics.

In 2004, in response to a court ruling, Mayor Richard M. Daley’s administration dropped Asians from the city’s minority contracting program. Over the next several years, Tuyet led protests and a legal fight against the decision, and the city returned Asian Americans to the contracting program in 2007.

During this time, I ran into Tuyet at a gathering. We started what turned out to be a years-long conversation about City Hall, often conducted over breakfast at an Uptown diner or at her condo, where she specialized in making waffles. I was covering local politics, and in confidence Tuyet would share outrageous stories about her attempts to lobby alderpeople. Once she emailed me after I had an exchange on TV with the alderman of the 50th Ward, a holdover from the old Democratic machine who’s since died.

“I’ve been on and off sick, so stayed home yesterday, mostly asleep with channel 11 on,” she wrote. “Did I hear you yelling at Bernie Stone? Or was it all a wonderful dream….”

Asian Americans Advancing Justice grew in size, influence and reach. Tuyet hired more organizers and built a presence in Springfield. She demanded answers from elected officials and they had to respond.

When a political stalemate left the state without a budget from 2015 to 2017, Tuyet led a team into a meeting with then-Gov. Bruce Rauner to make sure he understood the human cost of shutting down social programs. Her message: “Our communities are not a bargaining chip.”

“We had also orchestrated a couple hundred people outside that meeting wearing T-shirts that said, ‘We are essential,’ and we could hear them chanting” as the group made its case in Rauner’s office, said Andy Kang, the legal director for Advancing Justice at the time. “It was scary for a lot of folks, but her being there, her presence and confidence, gave people that extra courage to do the right thing.”

In 2018, after nearly two decades, Tuyet stepped away from Asian Americans Advancing Justice, forming her own consulting firm to continue community building. Kang succeeded her as executive director and now leads a national campaign against anti-Asian hate. Advancing Justice continues to shape laws and policies that expand civil rights.

That’s all part of Tuyet’s impact. As I learned from talking to some of her friends and former colleagues the last couple weeks, she mentored dozens of people and inspired many more. Her friends and allies are devastated by losing her, and more committed than ever to cause the kind of trouble she believed in.

I keep recalling another image of Tuyet. It’s from back when we were freshmen — teenagers — and we had no idea what we would actually end up doing with ourselves. Tuyet was an art major, and I sometimes saw her making her way to or from classes, moving steadily with her limp while carrying an easel pad that seemed as big as she was.

It could not have been easy. Tuyet just kept going where she had to go.

Listen to the Block Club Chicago podcast: