When Shaista Kazmi’s mother-in-law came to live with her family, they rotated through a series of different home care workers. Although each one tried to engage her mother-in-law, frustration settled in.

“She couldn’t understand them. They couldn’t understand her,” Kazmi said. “Not only the language, but then culturally there were things.”

Kazmi, who also took care of her own three small children, including a newborn, would prepare meals for her mother-in-law, but the home care worker did not understand how to heat up the different components. There were other missed cultural nuances, like when a worker would interrupt a family member during prayer.

Kazmi called AARP and other organizations for help, but “there was nothing” for her, she said. Instead, they suggested she call her temple or mosque, but those are places that offered prayers and calendars of services, not the resources she needed.

READ MORE: A visit to this market turns up Ramadan decorations and growing Muslim visibility in Michigan

Filial piety and respect for elders are important cultural values in Asian American and Pacific Islander cultures, and AAPIs are more likely to resist placing their elders in institutional facilities.

More than 60 percent of Asian American and Pacific Islander caregivers of someone 50 or older are providing care to a parent, according to a 2020 AARP report. That is higher than any other racial group. Almost two-thirds of AAPI caregivers also felt that they did not have a choice in becoming a caregiver, the report found, and 62 percent of AAPI caregivers expect to have some future responsibility.

About a quarter of Asian Americans live in “multigenerational households” or homes with two or more generations of adults aged 25 or older, according to a 2021 survey from Pew Research Center. That is a share on par with Black and Hispanic Americans who also live with multiple generations under the same roof — higher rates than the 19 percent of Americans overall in a similar household arrangement.

Many people like Kazmi struggle to find the resources to provide that care.

By relying on friends and family connections, Kazmi was able to find caregivers who understood the cultural nuances to better support her mother-in-law and, later, her father, who was diagnosed with a rare neurological disorder.

“Our parents have done so much for us,” she said. “The least I can do is try to find caregivers who are culturally similar, who can help our loved ones age in place with dignity and respect.”

Creating a space to age with dignity and respect

After her struggles finding the right caregivers, Kazmi opened a home care agency about 10 years ago in West Bloomfield, Michigan. Apna Ghar Home Care, whose name means “our home” in Hindi and Urdu, offered the kind of linguistically and culturally competent services she felt was missing when trying to find the appropriate care for her family members years ago.

Through word of mouth, she slowly began to get clients seeking to help their Asian American and Muslim American elders, and not only in Michigan, but across the country.

The agency rebranded this year as Sukoon Care with the help of a family friend whose parents had also received care at the business, with a focus on Asian American and Arab American elders.

READ MORE: How gardens enable refugees and immigrants to put down roots in new communities

Kazmi remembered one client who had three sons. She had a Christian Pakistani American caregiver who made her dosa and sambar, and two Indian American caregivers who performed Indian classical dances for her in her room.

Kazmi said the client called her to praise the companionship provided by the caregivers, saying they gave her hope.

“I swear, that’s the only reason this company is running,” Kazmi said of these blessings from clients.

Families of elders needing home services also said a bilingual or culturally competent caretaker helps give them peace of mind, “so that by the end of the day, when you come home, things are already kind of set in place,” Kazmi said, allowing quality time.

Why more training is needed for caregivers

To address the caregiving needs of Chinese American elders in Metro Detroit, the Association of Chinese Americans is launching a pilot program to improve the training for health care providers and families in caring for elders.

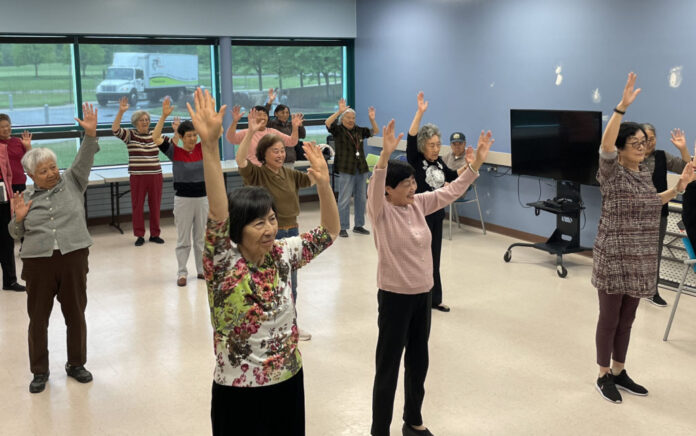

The nonprofit serves the Chinese and Asian Pacific American communities by providing year-round programs and services for seniors throughout the Metro Detroit area.

Executive Director Peggy Du said at least two families come to the nonprofit each week to ask for help finding a Mandarin or Cantonese-speaking caregiver. A search through the state’s health department network often turns up empty. Many families taking care of elders also have young children, Du said, adding that these overstretched caregivers must take care of their mental health, too.

Michigan State University professor Fei Sun talks with Chinese American seniors about healthy aging and caregiving at a health fair at the Chinese Community Center in Madison Heights, Michigan. Photo courtesy of Fei Sun

The pilot program’s curriculum is being developed by two Michigan State University professors whose work focuses on improving the quality of life for older adults. The training will include basic knowledge of geriatric symptoms and illnesses, like dementia and stroke, and the legal and ethical considerations in caregiving. The program will also consider Chinese norms, as well as some cultural taboos.

With regards to food, Du said some seniors want to eat healthy but they do not like spaghetti or mac and cheese.

“We can change it to some other more Asian friendly foods, like noodles or porridge, but still keep the nutrition part that is good for those seniors,” she said.

The demand for caregivers who are fluent in both English and Mandarin or Cantonese often exceeds the available supply, said Fei Sun, one of the co-creators of the new program,

“This gap means that many families are struggling to find qualified professionals who can communicate effectively with their loved ones and provide culturally competent care,” he said in an email to PBS News.

In that void, some families are forced to rely on their own network of Chinese-speaking friends, family, or church members to fill this need, but it is “not a sustainable solution and does not always provide the level of professional care required,” he added.

READ MORE: New citizens in Michigan share what voting means to them

Beyond providing care that is respectful and appropriate to elders’ cultural norms, “caregivers who share a common language and cultural understanding can help bridge community barriers, making the care process smoother and more effective,” Sun said. “When elders feel understood and respected, they are more likely to engage in their care and adhere to treatment plans, leading to better overall outcomes.”

The program’s creators also plan to develop a handbook that could then be shared with other community leaders to adapt for other Asian American communities and languages.Through the new program, Du also hopes to help people who may want to reenter the workforce. The nonprofit already offers English as a Second Language classes and Chinese language and culture classes. Participants in the program can also learn medical English in the training. At 50 to 55, “they are still kind of young,” she said.

“They still have a chance to go back to the workforce. Maybe they need some training, some skills to help them,” she said.

Creating senior living communities

Arun Paul is the founder of Priya Living, which creates independent senior living communities focused on, but not limited to, South Asian cultures and communities. There are Priya Living communities in California and India, with plans to expand to Michigan and Texas, but Paul said he and other businesses are currently having difficulty developing new senior living communities, citing rising construction costs and interest rates.

Before starting his venture into these communities, Paul talked with elders around the country. He took note of the groups of elders in suburbs who gathered every week at the local park or community center.

“I just went and talked to these groups of aunties and uncles, and I heard the same thing: People really enjoy each other’s company and that gives them life,” he said.

South Asian American seniors and family gather to celebrate a birthday in the courtyard of a Priya Living community in Santa Clara, California. Photo courtesy of Arun Paul/Priya Living

Paul grew up in Southern California as an only child. He has been aware of the rich cultural connections that his parents left behind when they immigrated to the U.S. from India in the 1960s.

When he created Priya Living, he thought of his parents and the close companionship he saw among family and friends in India, like at a wedding or at the temple. He wanted the community’s complexes painted in the vibrant colors of the country, with lots of cultural and educational programming so that people would not stay isolated inside their apartments.

Paul’s parents, both of whom have since died, moved into the first Priya Living complex in Santa Clara, California. He noticed an immediate change.

“It used to be, when they lived in their old house, I would call, and my mom reliably would pick up the phone,” Paul said. Once she moved into the new complex, he could not get a hold of her. “I would leave her voicemails that don’t get responded to for three days because she had so much to do. She was having a great time.”

READ MORE: How violence against Asian Americans has grown and how to stop it, according to activists

For Paul, it is important to help nurture communities where Asian Americans did not feel like the “other.”

“At some level, there’s a safety and security element,” he said. “We want our communities to be a lot more than that, like actually helping people self actualize … where people can feel comfortable, accepted, understood.”

One of the most memorable pieces of feedback Paul heard was from the daughter of a resident. After her mother had died, the daughter thanked him for giving her mom a “second childhood.”

“Ultimately, it’s about the relationships between people and our communities and how strong those are,” he said.