By Samantha Pak

NORTHWEST ASIAN WEEKLY

When Susan Tate Ankeny was asked to write a book about Hazel Ying Lee (1912-44), it was because the publishing company was looking for someone to tell Lee’s story, and they liked Ankeny’s style of writing in her debut book—narrative fiction that reads like fiction. But what they hadn’t realized was that as a Portland, Oregon native, she was already familiar with Lee, as she and the late pilot are from the same city.

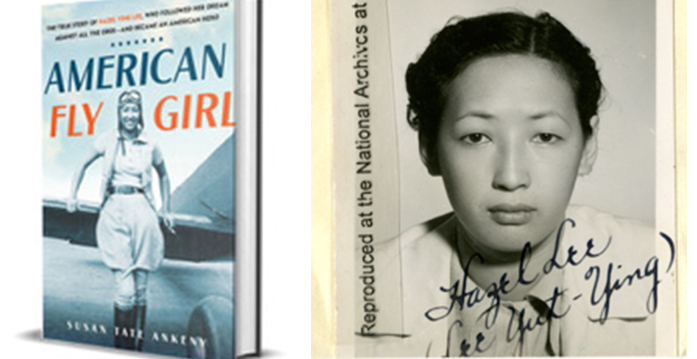

Lee was the first Asian American woman to earn a pilot’s license, join the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs), and fly for the United States military—all amid widespread anti-Asian sentiment and policies. Ankeny’s book, “American Flygirl,” was published in April and chronicles Lee’s life as she went from the daughter of Chinese immigrants growing up in Portland, to becoming trained in combat flying, and where that took her.

“She was really remarkable,” said Ankeny, who now lives in Vancouver, Washington.

A natural pilot

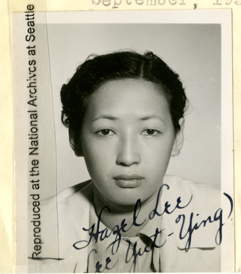

Hazel’s affidavit photo, 1937: Chinese Exclusion Act case files, RG 85, National Archives- Seattle, Lee Yuet Ying (Hazel Lee) case file, Seattle, Box 582, 7030/5149, and Box 710, 7030/10411.

Lee joined a flying club in 1931. It was for the Chinese American men in Portland’s Chinatown, but Ankeny said she was able to get one of the instructors to believe in her. Within a year, Lee earned her pilot’s license at the age of 19. Shortly after that—around 1933—she was among 200 Chinese American pilots recruited from Chinatowns throughout the United States (34 of which were from Portland) to fly and fight for China against invading Japanese forces. While in China, these pilots were required to join the Chinese air force, and many died in combat.

“Here are these young people. They’re American. They were born here. They go over to China, to fight and die, to help China keep its sovereignty—its freedom,” Ankeny said. “It’s an amazing story, just that part of it. [Lee] was involved in that, and then came back to this country prior to World War II, thinking with her skills—she was an incredible pilot—that she would be accepted into the U.S. military.”

Lee was not. After returning to the United States in 1938, Lee asked to join the military, but she was turned down. And after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Ankeny said Lee was sure they would take her, but the U.S. military still turned her down—all because she was a woman. Instead, Lee joined the WASPs, a program that trained women to replace men in non-combat positions so those men could go overseas to fly and fight in combat. Through this program, they released more than 1,000 men for combat.

A dangerous job for women

Lee and other women in the WASPs program (flying for the military, not with the military) ferried aircraft—including fighter planes and bombers—from when they came off the assembly lines, and flying them to flight schools, or to the coast to go over to Europe.

“These planes coming off the assembly line were not always okay,” Ankeny said. “There were lots of dangerous situations these women were put in, and 34 of them died—all preventable…These planes were being made very, very quickly. Lots of times, engines would fail, and these women were the first to get the plane, so they didn’t know if something wasn’t quite right. You know, accidents. One man ran into a woman. He was kind of fooling around with his plane, and he nicked her, showing off.”

In addition to being one of their best pilots, Lee, a born leader, was also one of the leaders of the WASPs. And Ankeny said, “She would have done great things,” but on Thanksgiving in 1944, when she was bringing an aircraft to Montana, another pilot who didn’t have a working radio, and didn’t see her, landed his plane on top of her. They both crashed, and while the male pilot was able to climb out and live, Lee only survived three days before succumbing to her injuries. She was 32.

Virginia Wong and Hazel Lee on Swan Island during their training, 1933-1934. (Courtesy of Museum of Chinese in America, New York City)

Giving Lee the attention she deserves

Although Ankeny was aware of Lee before writing her book, the 63-year-old learned a lot while researching the pilot. She said she wasn’t surprised by the prejudice and discrimination Lee faced as a woman—especially since that was the bigger issue and many of the rules at the time were against her being female—but was surprised by the discrimination Lee and other Asian Americans faced during that time. Ankeny also didn’t know or understand the extent of discrimination that had taken place in her own hometown because “it is conveniently not spoken of, because it’s embarrassing. They want to forget how badly they treated their fellow citizens in Portland.”

As a white woman, Ankeny said she understands being subjected to sexism, but she’s not going to pretend she understands what it’s like to experience racism. She can read about it and research it all she wants, but she can never know what it feels like. This was something Ankeny expressed concerns about when first taking on the project, but she said her being white might have actually helped her in writing Lee’s story.

“Maybe, because I can’t imagine it, helped me write it, in a way. Maybe I picked up things,” she said. “Hazel seemed to take everything in her stride. Somebody that wrote a review about my book said they were amazed at how she just seemed unfazed by her treatment. Whereas, when I’m seeing it, I’m horrified, and I think it’s because I have not been treated that way.”

Her hope with “American Flygirl” is that other writers—especially Asian American or Chinese writers—can take Lee’s story further, pointing out that she didn’t go to China and do the work there.

“I’m not the only voice, but I hope I brought her to attention, to the public’s attention,” she said about Lee. “She deserves that.”

Ankeny added that many people who have read her book have told her that they’d never heard of Lee, so she is happy to let them know. In addition, there are members of Lee’s family, who still live in Portland and didn’t know much about her because after she died, the family stopped talking about her, because it was too painful. Ankeny said to have a story for Lee’s family is the biggest honor for her.

Through this process, Ankeny has become inspired by Lee. Describing the pilot as the greatest inspiration of her life and thinking about her daily, she spoke about what she would do.

“When I’m faced with discrimination, I’m not going to back down. Because Hazel would not have…A woman who didn’t let race or gender get in her way, and she wasn’t violent,” Ankeny said. “She just said ‘no’ to the barrier. She just went right through them.”