In his 2022 book Model Minority Masochism, scholar Takeo Rivera argued that the influx of Asian immigrants to the United States after 1965 and the trial of Vincent Chin’s murderers in the early ’80s wholly transformed Asian-American identity. The once-radical term steadily devolved from its leftist origins into a neoliberal form of ethno-national pride. Forty years later, we are one of the fastest growing racial groups in the country, encompassing communities as varied as the Stop Asian Hate movement, which has been criticized for its demands for enhanced policing, and progressive political organizations like 18 Million Rising or Korea Peace Now. With such a wide range of politics, goals, and strategies, not to mention cultural practices and heritage, is it possible for Asian-American identity to be a political home for all of us?

Against this backdrop, Legacies: Asian American Art Movements in New York City (1969-2001) at New York University’s 80WSE Gallery is an especially timely exhibition, examining through art and archival material how Asian-American identity resists a unified political or aesthetic narrative. Organized chronologically, the show brings together the work of over 90 Asian and Asian-American artists who lived or spent time in New York between 1969 and 2001, with a particular focus on three arts organizations to which many of the artists were connected: Basement Workshop, Asian American Arts Centre, and Godzilla: Asian American Art Network.

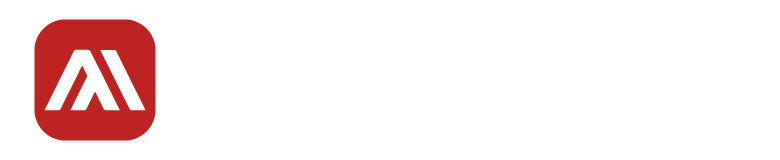

From abolitionist and anti-war protest art by Basement Workshop to the biting institutional critique by anonymous activist group PESTS and Godzilla’s request for more representation at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Legacies reveals a series of varied and, at times, conflicting strategies for navigating the art world, whether through ethno-nationalist pride and self-segregation, noncooperation and critique, or institutional inclusion and assimilation. This feels refreshing, especially when related exhibitions ignore the contradictory nature of Asian-American identity and instead function as surface-level celebrations of community.

Witnessing such a convening of three decades’ worth of work highlights how Asian Americans have largely been the sole custodians of Asian-American art history, diligently caring for and preserving it. It was fascinating to see certain names pop up repeatedly throughout the exhibition, sketching out a family tree and network of relationships I was pleased to see a painting by Margo Machida, who I recognized primarily as a curator and writer. A co-founder of Godzilla in the early 1990s, Machida would go on to curate the landmark show Asia/America in ’94, which originated at the Asia Society and Museum, and write several important books on Asian-American art history.

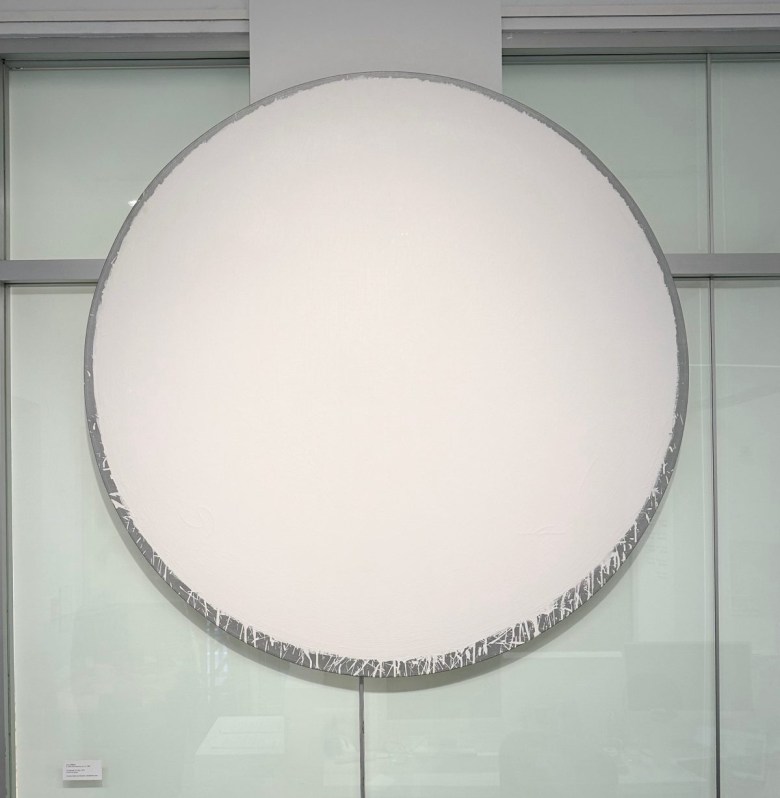

Artist Arlan Huang is another recurring presence, with posters and album covers from his Basement Workshop days, a 1992 sculpture from his time in Godzilla, and a photograph by Corky Lee from his personal collection on view. Printmaker and activist Tomie Arai, also part of Godzilla, is represented by two silkscreen posters made at Basement Workshop. Arai continued her political work by co-founding Chinatown Art Brigade in 2015, and both she and Huang were among the co-writers of the letter that would eventually result in the cancellation of a planned Godzilla retrospective at the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) in 2021. The disagreements between the leadership at MOCA, the protestors, and even internally among members of Godzilla offer a succinct introduction to the political disunity of the community, even as all sides would likely say they are working in the best interest of Asian Americans.

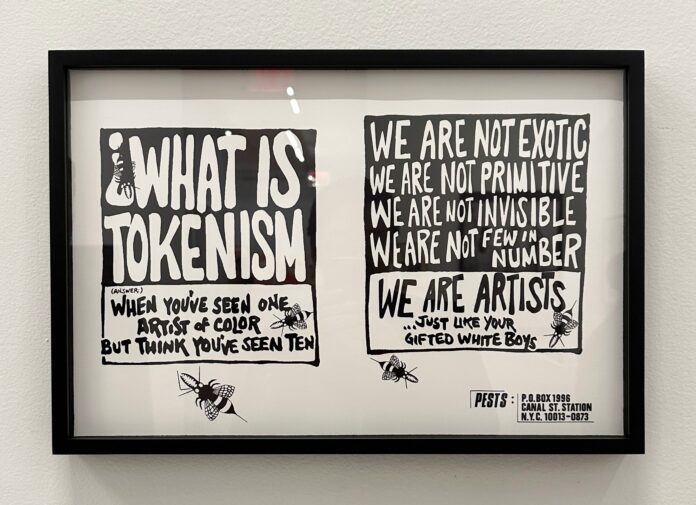

In the lobby hangs a large painting by Leo Valledor from 1970 in which a loosely rendered white circle nearly fills its circular canvas. Paint drips from the bottom of the shape, threatening to spill over the edge of the canvas itself. Legacies functions similarly; its tightly focused container of race, geography, and time highlights the impossibility of encircling the “leaky” category of Asian-American identity, as Sharon Mizota described it. To return to my original question, Legacies argues that Asian-American identity is too broad an umbrella to be a political or aesthetic home for all of us. What demands closer analysis is why we expect or desire it to be.

Legacies: Asian American Art Movements in New York City (1969–2001) continues at 80WSE (80 Washington Square East, Greenwich Village, Manhattan) through December 20. The exhibition was organized by 80WSE Curator Howie Chen, Jayne Cole Southard, and Christina Ong.