As the Trump administration prioritizes reaffirming American strength, its focus appears to be on economic decoupling, military modernization, and burden-sharing among allies in the Indo-Pacific. The escalating tensions between the United States and China under Trump could have significant repercussions for Southeast Asia, given the region’s strategic position between the two superpowers, and close economic relations with both. Despite concerns over the “America First” policy and a more assertive stance against China, ASEAN nations have largely adopted a pragmatic approach, seeking to engage with the US where interests align. However, the protectionist economic policies of the new Trump administration could negatively affect the economic outlook for Southeast Asian countries, whose growth and prosperity have largely relied on an open, rules-based, global trading system. With Trump’s new transactional approach, questions arise for ASEAN about the true value of seeking a rapprochement with the US, which raises the cost of defense cooperation and prioritizes internal economic interests over political relations with the region.

Why it matters

- Pivot to MAGA. In recent years, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam have emerged as “connector states”, benefiting from the “China Plus One” strategy, where companies seek alternative production hubs outside China. While this has granted them greater economic stability, many of these countries maintain significant trade surpluses with the US. Trump has ordered his advisors to address the US trade deficit, primarily through increased tariffs on partners in response to what Washington views as unfair trade practices. India, Thailand, and South Korea are among the most vulnerable to tariff retaliation; similarly, Japan, Malaysia, and the Philippines will be likely targets. Furthermore, US budget cuts to USAID have already led to the suspension or downsizing of numerous development programs in the region. Trump second term could further curtail funding for critical initiatives, reducing US soft power and influence in Southeast Asia.

- Goodbye IPEF? Trump’s foreign policy approach has been personalistic and bilateral, marking a sharp departure from the multilateral strategies of Biden and Obama. Just as Trump withdrew from Obama’s Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, a second term could see him pulling out of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), which Biden launched to strengthen industrial ties with regional partners. This withdrawal could result in a situation mirroring the one that followed Trump’s retreat from the TPP, whereby US absence led ASEAN nations to strengthen economic cooperation with China. If the IPEF collapses, Beijing could further expand its influence through initiatives like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

- Big Economic Losses. Among ASEAN nations, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia have been among the major indirect beneficiaries of US-China competition. They have successfully attracted investments diverted away from China, as businesses sought politically viable alternatives. However, a return of Trump’s protectionist trade policies—including potential tariffs on ASEAN exports—could disrupt this advantage. Vietnam’s economy, heavily reliant on exports to the US, could suffer from stricter trade measures. Similarly, Malaysia and Indonesia—which have leveraged their strategic position for economic growth—could face greater uncertainty in trade relations. Meanwhile, Indonesia has taken a multi-vector foreign policy approach, like India, by engaging in active non-alignment. This became clear when Jakarta decided to join BRICS, while continuing its roadmap to access the OECD, signaling a desire to diversify its strategic partnerships and reduce reliance on any single superpower.

- More defense, but for whom? Another major concern for ASEAN nations is the potential reduction of the US military presence in the region. The US currently plays a key security role in the South China Sea, where Chinese claims of sovereignty conflict with those of littoral Southeast Asian nations. Countries most vulnerable to this shift include the Philippines, which under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has reinforced military relations with Washington. In recent years, Manila has experienced repeated clashes with China’s coast guard, raising fears of an escalation. If the US reduces its commitment, ASEAN claimants in the South China Sea—like Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines—could feel increasingly exposed to Chinese threat of aggression. The Philippines, in particular, may re-evaluate their alignment with the US if Washington signals disengagement, potentially seeking alternative security partners such as Japan, Australia, Canada, and India.

OUR TAKE

A second Trump presidency introduces new challenges in an already strained international system. His deep skepticism towards alliances and preference for unilateralism could erode traditional partnerships, forcing US allies to reconsider their strategic positioning. This shift can lead to a reassessment of security commitments and multilateral cooperation, particularly in regions where US influence has been a stabilizing force. While ASEAN nations may reconsider their strategic positioning, Washington remains crucial for regional security, providing military support and defense cooperation. Economically, the US remains a key investor and market for ASEAN states, balancing their strong trade relations with China. However, aligning with Washington could become increasingly costly and difficult, and doubts could emerge about the US’s long-term commitment to regional stability. While the US remains crucial for security—providing military support and defense cooperation—and a key economic partner, these challenges could create fractures within the bloc. Member states with differing economic and strategic interests may differ on how closely to align with the US, putting ASEAN’s cohesion to the test. In 2025, Malaysia has assumed the ASEAN chairmanship, tasked with reinforcing unity as US-China tensions persist. With Washington’s reliability in question, could this moment serve as a catalyst for a more politically cohesive and strategically independent Southeast Asia? That remains a critical question.

SPOTLIGHT: For Trump, a steel conundrum hangs over the US-Japan alliance

As Trump has returned to the White House for his second term, Japan may be looking for a deal after the Joe Biden made a controversial decision that soured US-Japan ties. On the 3rd January, the former US president announced his decision to block Nippon Steel’s $14.9 billion bid to acquire US Steel, citing national security concerns for the US. This decision was unprecedented, as it marks the first time a Japanese acquisition in the country has been banned. Since then, Nippon Steel and US Steel have filed two lawsuits. What puzzles the Japanese business leadership is the “national security” motivation, given the tight strategic relationship underpinned by a mutual defence alliance, as well as Japan’s position as top investor in the US. Now, with Trump back in office, a new political possibility may open as demonstrated during the meeting with Prime Minister Ishiba in early February. Despite Trump’s alleged opposition to the acquisition, he announced that he would welcome a heavy investment from the Japanese company, short of a majority stake. Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi has later revealed that Nippon Steel is considering a “bold proposal”, and Trump may be eyeing for a news-making deal amid increased tariffs on steel imports. The ingredients for a grand bargain are in place, and the other Indo-Pacific partners of the US will be watching for clues: is Trump willing to reconcile his protectionist agenda with the necessity to keep US allies close to collectively confront China?

EXPERTS’ VIEWS

How are Indonesia and the other ASEAN countries preparing for years of geopolitical tensions under the new Trump administration?

As geopolitical tensions rise under President Trump’s new administration, Indonesia and ASEAN must navigate an increasingly transactional and polarised global order. Trump’s return signals a resurgence of unilateralism and economic decoupling from China—an outcome the region cannot afford. Indonesia, under President Prabowo Subianto, seeks to maintain its multi-aligned independent and active foreign policy while advancing economic and security interests. Its recent accession to BRICS, framed as South-South cooperation, also serves as leverage with the West. However, rising US-China-Russia tensions could strain ties with Washington. Trump’s threats of steep tariffs on BRICS members, particularly over de-dollarisation efforts, raise concerns about restricted market access and withdrawing military support, requiring Indonesia to recalibrate its position. For ASEAN, great power rivalries threaten regional cohesion. With Trump sidelining multilateralism in favour of bilateral arrangements, ASEAN risks fragmentation, potentially pushing some states toward minilateral groupings like the Philippines with the US allies of Japan and India through SQUAD as the former needs to seek support to counter China’s aggressive behaviour in the South China Sea. As such, safeguarding strategic autonomy will be critical.

Fitri Bintang Timur, CSIS Indonesia

How will Trump’s foreign policy and the new US-China relation affect the future of ASEAN?

Donald Trump’s return to the White House and the (re)implementation of a transactional ‘America First’ approach to foreign policy has once again created a deep sense of uncertainty for ASEAN and its member-states. Previous experience from his first presidency suggests that ASEAN itself is likely to be sidelined as the administration returns to a bilateral approach to the ‘art of the deal’. Malaysia’s assumption of the ASEAN chairmanship for 2025 and a (forthcoming) statement from the association condemning Trump’s recent proposal to remove Palestinians from the Gaza Strip to neighboring countries—alongside Kuala Lumpur’s strident critiques of Washington for its complicity in what it characterizes as genocide—is unlikely to improve ASEAN’s standing in the eyes of the White House. Tariff and counter-tariff warfare between the United States and China as part of strategic competition between the two powers creates both opportunities and threats for the region. Tariffs put in place during Trump’s initial presidential turn and maintained under the Biden administration saw an influx of Chinese capital and manufacturing capacity as companies shifted their factories in the region to avoid being slapped by additional taxes, a development likely to intensify with more protectionist measures looming on the horizon. But at the same time, the likelihood of Trump deploying tariffs against Southeast Asian countries and ASEAN—given he was willing to do so with close ally Canada—poses a threat to a region still highly dependent on exports to the US. Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar have already made clear their closer ties with the People’s Republic. In contrast, Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam (many of whom are currently still in dispute with China over its ten-dash line claims over the South China Sea) are likely to continue the ongoing process of economic and security diversification with partners like Australia, Japan, and South Korea.

Bernard Z. Keo, Geneva Graduate Institute

WHAT AND WHERE

China and AI: Xi’s Special Envoy attendsthe Paris Summit amid DeepSeek aftershock

The US stock market was recently shook by the Chinese company Deepseek’s release of a new AI model, which it claims was developed at a significantly lower cost than its competitors.. This was received as a potential new Sputnik moment: daily downloads of the app immediately overtook those of ChatGPT, while several countries swiftly banned or limited its use for government officials. Many investigations have been launched since then under allegations of unfair practices. This happened few weeks before the beginning of the third edition of the AI Summit, which took place in Paris on February 10th and 11th, where the debate was focused on the geopolitics of AI and the future of the industry at the global level. Hosted by France’s Macron and India’s Modi – that will host the next edition of the summit –, the event saw the participation of government officials, entrepreneurs of the tech sector and researchers of the field from over 80 countries. Among them, the Summit was attended by US Vice-President J.D. Vance, who openly asked the EU not to “strangle” the sector with regulation, along with the Chinese Special Envoy Zhang Guoqing.

South Korea is on the brink, as the political crisis deepens further

After Yoon’s martial law bid in early December, South Korea has plunged into political turmoil. After the impeachment of President Yoon Suk-yeol on the 14th December, Prime Minister Han Duck-soo took his position. However, on the 27th December he also was impeached by the opposition-controlled parliament for refusing to appoint three justices to the Constitutional Court. The next in line was Finance Minister Choi Sang-mok, who has faced enormous pressure from his own conservative party for ceding to the opposition’s demand to fill two of the three vacant seats in the Constitutional Court, as well as from the leading opposition party to facilitate the arrest of Yoon. Political tension can easily turn into social instability: after the arrest of the impeached President on the 15th January, a crowd of hundreds of supporters stormed into the court that confirmed his detention. Yoon called his arrest “illegal” and has refused to collaborate with the investigation for insurrection filed against him, while on the other hand he has denied any wrongdoing in front of the Constitutional Court that is examining his impeachment case. Yet, as the crisis drags on, an unexpected outcome has been the resurgence of the conservatives in the polls, after the dramatic fall that followed Yoon’s martial law announcement. Should the Constitutional Court confirm the impeachment of Yoon as early as March, new presidential elections will be arranged in 60 days: democrats may retain a lead in the polls, but the country remains on a knife’s edge.

China-Pakistan relations on a positive track, while domestic politics are shaken by Khan court case

After a 2024 positive round of high-level bilateral talks between Beijing and Islamabad 2025 appears set to sustain and enhance this trend. Ministers of Interior Qi Yanjun and Mohsin Naqvi met on February 4, and discussed common procedures on law enforcement, intelligence sharing and the use of paramilitary forces. President Xi Jinping and President Asif Ali Zardari met on the same day; on the table were once again prospects for further cooperation on economic issues and coordination in response to domestic and international terrorism. However, while the bilateral dialogue keeps improving, tensions are rising about episodes of violence and harassment that Chinese nationals have been suffering in Pakistan, that escalated after 13 people were killed in the explosion of a bus in 2021. Meanwhile, the court case of the then PM Imran Khan reaches another turning point: on January 17, he and his wife Bushra Bibi were sentenced respectively to 14 and 7 years for a land corruption case: government officials report “undisputable evidence” that the two have accepted the bribe of a real estate tycoon involved in a money laundering investigation, although former PM claims the case is a “political witchunt”.

One for the tariffs, and tariffs for all: Trump 2.0’s economy and China’s response

As expected, Donald Trump’s return to office has reignited trade tensions with China. Among the many executive orders signed by Donald Trump during his first weeks in office various target China. Just few days after the beginning of his mandate, the new US President announced 10% additional tariffs on all imports from China, citing Beijing’s alleged role in fentanyl trafficking in the US as reason for this retaliation. Chinese authorities did not wait for long to respond launching an antitrust probe against Google and announcing new 15% tariffs on imports of US coal and liquefied natural gas, 10% tariffs on agricultural machineries and crude oil, as well as imposing restrictions on exports of raw materials to the US. On January 10th, Trump imposed additional 25% tariffs on aluminium and steel, that hit severely trading partners not only in Asia (like Japan and South Korea), but also in Europe (like Germany). China’s tariffs affect $14 billion in US imports: compared to the US “blanket” tariffs, China’s targeted measures are seen as leaving room for negotiation with the competitor. Though China is more prepared for a trade war by leveraging its dominance in key supply chains, its slowing economy remains a major vulnerability. Further escalation and new tariffs risk undermining Chinese exports, one of the country’s remaining economic lifelines. Given these constraints, Beijing may find negotiating with the Trump administration a more beneficial path than direct confrontation.

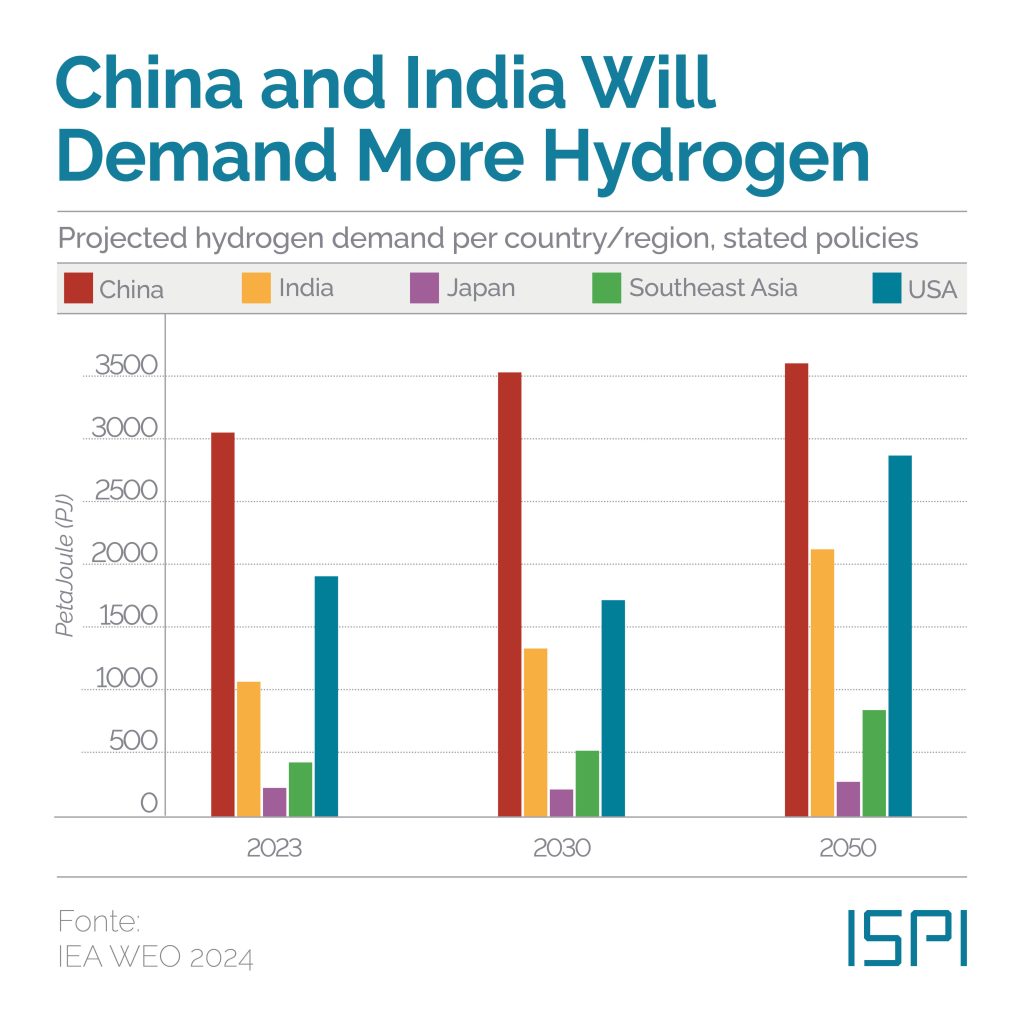

TREND: Hydrogen Demand in Asia (2023-2050)

Data from the IEA World Energy Outlook highlight how the demand for hydrogen as a source of energy is expected to grow in the future. China and India will lead the rise in demand, with China growing from slightly over 3000 PJ a year to more than 3500 PJ in 2050. India will follow, with a total demand that will more than double in the next 25 years, jumping from about 1000 PJ a year in 2022 to over 2000 PJ in 2050. Similarly, Southeast Asian countries will double their request, even though their total demand is expected not to reach 1000 PJ by mid-century. Furthermore, the 2024 Global Hydrogen Review has shown how production will follow a similar path in the upcoming years. Japan will maintain very low levels of production, surpassed by South Korea and Southeast Asian countries, while India will lead the regional production, with over 3000 kt (more than 4000 PJ) of hydrogen produced yearly through its main 8 projects; China follows, with the biggest project of the subcontinent expected to produce more than 2000 kt (about 300 PJ) per year in Baicheng (Jilin).

WHAT WE ARE READING

‘New class war’ comes for Xi’s China as public frustration mounts

Which goods are most vulnerable to American tariffs on China?

“Challenges and Priorities for Myanmar’s Conflicted Economy”

Malaysia’s Anwar backs down on protest rules, activists hail move as ‘a victory’