By Aviraj Gokool

(This is part of our ongoing series, Lost Kinjo– a look at the more than 40 Japanese communities that disappeared after World War II. It is supported by funding from the California Public Library Civil Liberties Project and the Takahashi Family Foundation.)

Among the trendy cafes and rows of preserved colonial Spanish style buildings in Santa Barbara, CA sits the El Presidio parking lot. There sunlight shimmers down on a lonesome sign colored in light tan, red, and navy blue.

Upon closer inspection, the sign reads “JAPANTOWN (Nihonmachi)”. Under it is a brief description of the former community that thrived down the narrow road. Accompanying the words is a black and white picture of a grand hotel; The Asakura Hotel.

The Asakura Hotel was one of the first buildings established by Sentaru Asakura in downtown Santa Barbara. He, along with fellow Kumamoto-native families, the Fukushimas and Kakimotos, migrated together in the early 1900s. The hotel thrived as a popular destination for early Japanese settlers. Yet the Asakura Hotel’s significance was much grander than being just a simple hotel.

It provided affordable housing. It also became a destination for Japanese to celebrate their culture, offer immigration help and network with fellow Japanese Issei (first generation).

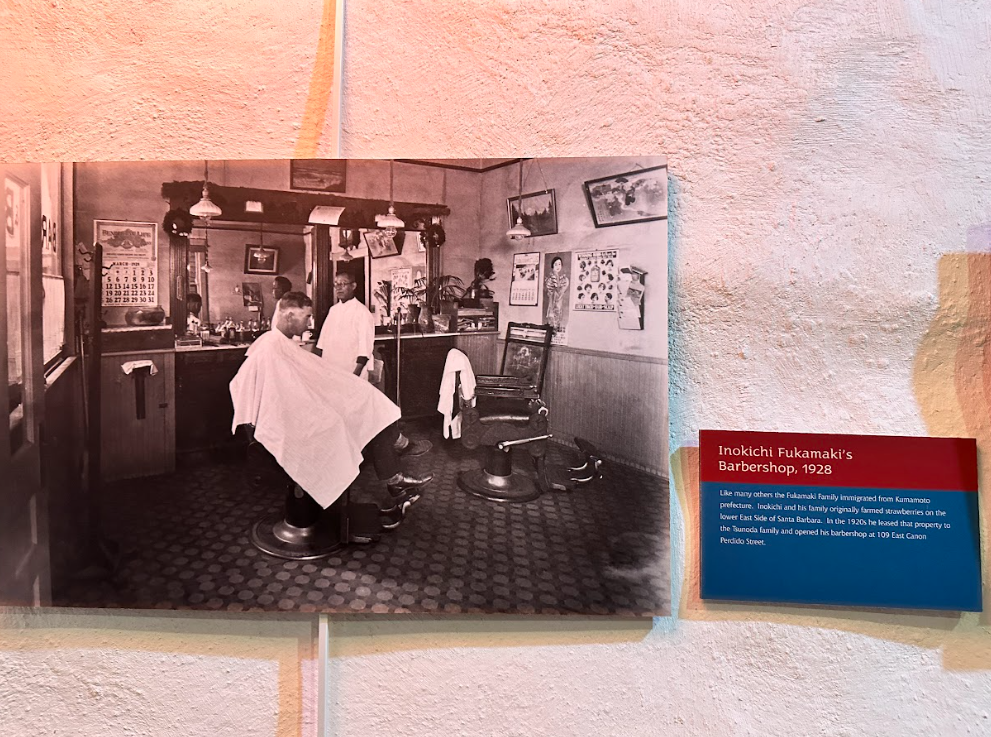

Over time, several shops that served the community opened in the immediate proximity of the hotel. Former tenants of the hotel opened a bathhouse, a Japanese grocery store, and a barbershop. This marked the early beginnings of Santa Barbara’s Nihonmachi. It’s thanks to the Asakura Hotel that around 500 Issei migrated and transitioned to Santa Barbara’s Japantown just before WWII.

The Japanese community quickly grew over the years. The Asakuras, Kakimotos, and Fukushimas collectively owned a large portion of the buildings in Santa Barbara’s Nihonmachi.

They owned farms, billiard halls, grocery stores, and barbershops. They also assisted in the foundation of the Japanese Buddhist Church and the Kumamoto Kenjinkai (prefectural association). The construction of these buildings were crucial to expanding and cultivating the Japanese community.

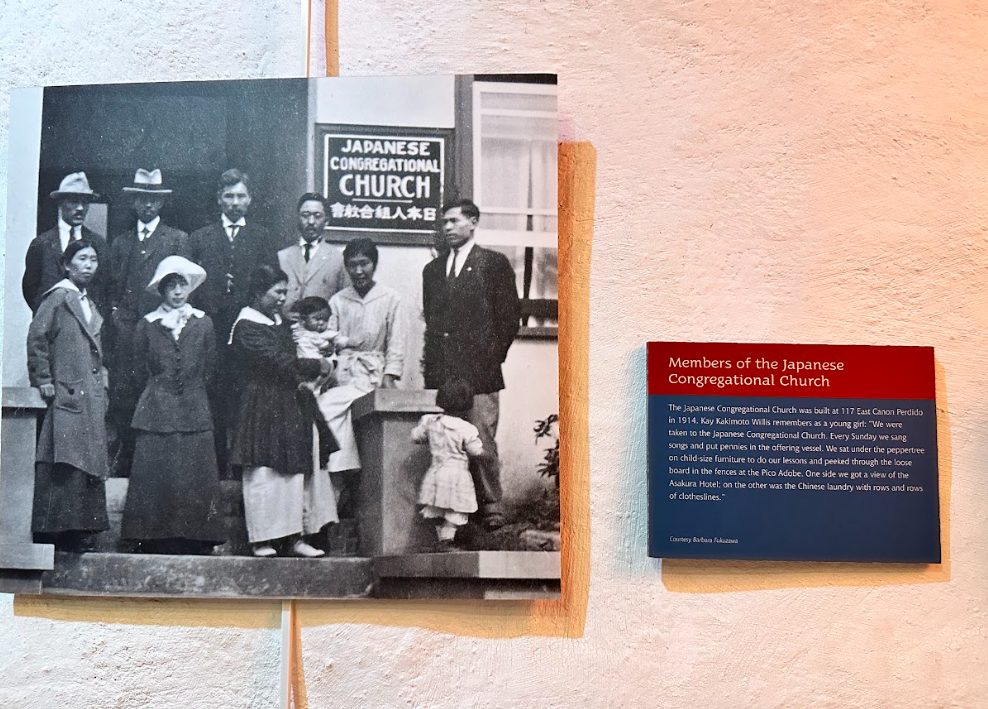

“A lot of life was organized around the Buddhist temple and Christian church,” Koji Lau-Ozawa, an archaeologist and anthropologist who worked on the history of Santa Barbara’s Nihonmachi, told AsAmNews. “There were also Kenjinkai. Those were pretty important social organizations where people went on picnics and did events.”

The Buddhist Church provided and arranged social groups for Nisei (second generation American-born Japanese). The church organized Japanese language instruction, judo classes and a baseball team for the kids. It also coordinated social groups and events like business associations, movie nights, and picnics. Meanwhile, the Kumamoto Kenjinkai served as a central community center for the Japanese community.

On Sunday mornings, beautiful bellowing voices singing in harmony echoed from the church. Children at Sunday school stared through fences to get a clear view of the Asakura Hotel on one side and a Chinese laundry store on the other.

During the afternoons, some joined picnic events, socialized at the community centers, or strolled through nearby flower fields tended by the local farmers. Others stopped by Inokichi Fukamaki’s barbershop, right next to the Asakura Hotel.

Meanwhile, kids and teenagers played in their respective sports leagues like the Japanese American Baseball League. Though the Nihonmachi occupied just one road, people were always active.

Along with the neighboring Chinatown, Downtown Santa Barbara flourished as a cultural center. Hand-painted traditional porcelain bowls with bamboo motifs, Japanese manufactured plates with phoenixes, and soy sauce directly imported from Japan were commonly used in households. Among these items, Law-Ozawa and his colleague, Dr. Stacey Camp, found remnants of billiard tables, porcelain tea cups, cream pots, and rice bowls.

“There is a series of almost unbroken, whole ceramic bowls of Japanese manufacturers that were found near where the old Buddhist temple was,” Lau-Ozawa said in his and Camp’s film, Sonzai: Japantown in Santa Barbara. “One of the theories is that this might be a reflection of caching; stashing these away intentionally… Usually when we find ceramics like that, they’re used, broken, and discarded. To find a large number of whole items is unusual and generally speaks to intentionally putting away.”

Lau-Ozawa further explains in his film that “American communities were stigmatized for any markers of Japanese identity.” People in ethnic enclaves were judged based on their activities, religious affiliations, and material culture. People would question their “American-ness” if people expressed their culture through their clothes or ate from Japanese traditional plates and dishes. Others would put a “percentage” on just how American people were.

Consequently, families were forced to choose between preserving their cultural identity or being white-washed by casting away their cultural items. “There was an incentive to hide that Japanese identity,” Lau-Ozawa explains in his film. “So this caching both may have been a phenomenon related to hiding away your valuable materials while you’re being removed to hopefully return to but also hiding away your identity.”

Though, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, it didn’t matter what percentage of Japanese people were. With the enactment of Order 9066, every Japanese family was turned into prisoners and forced into incarceration camps. Most Santa Barbarians were sent to Gila River in Arizona where camps were built on Native American land.

To every Issei and Nisei’s dismay, the order came as a shock. People took what they could and tossed or perhaps cached what they couldn’t. For most families, all they could fit in their luggage were clothes, brushes, and bedding.

Prison guards threw them into makeshift quarters that were essentially minimally furnished barracks. Families struggled with dusty sandstorms, hot, dry climates, and extremely small living quarters with little to no privacy.

With a little over 13,000 Japanese thrown into prisons, tension and unrest built. People came from an array of different backgrounds. Rural and urban residents mixed with Issei, Nisei, and Kibei (Japanese Americans born in the U.S. but studied in Japan). This generational and cultural divide contributed to the uneasy atmosphere. However, the War Relocation Authority (WRA) compounded the tension.

The WRA introduced a self-governing system to promote “democracy” within the incarceration camps by forming “a council consisting of representatives from each block.” These sorts of organizations were known as block councils. At Gila River only American citizens could run for these positions.

Issei, who were typically older and were the leaders in their former communities, could only take positions as block managers dealing with day-to-day disputes and allocations. Only the Nisei and American citizens were permitted to be a part of the community council which passes codes and regulations for the incarceration camps.

Similarly, friction and disputes increased as, again, only American citizens qualified to work at higher paying jobs, specifically at the camouflage net factory. Some worked in agriculture and war production but according to Densho, “a majority worked directly for the WRA in staff positions for the mess hall or hospital, the elementary and high schools, and as support staff for the administrators.”

“A lot of the Issei and kibei are boxed out of positions of authority. Some of it is around citizen requirements…” Lau-Ozawa told AsAmNews. “You couldn’t work in the factory unless you were a citizen so there was resentment between Issei and kibei because the Issei can’t get the higher paying jobs.”

Though, either consciously or not, the community fought against the WRA and the forced assimilation. Issei and Nisei both ate from traditional Japanese porcelain bowls and ceramics.

“If you look at the proportion of bowls to plates amongst that material culture, it matches the proportion of bowls to plates in the pre-Japan, pre-war assemblage,” Lau-Ozawa told AsAmNews.

In this way, people pushed back against institutional food practices Americans performed by preserving their own. Ironically, by condensing over 10,000 Japanese into one small area, their nationalism and cultural celebrations strengthened during their concentration period.

Farmers, artists, dancers, singers, and athletes all celebrated and embraced Japanese tradition. They kept cultural practices like the Obon Festival, writing haiku, or frequently holding sumo wrestling matches. Martial arts was also a widely popular activity not just in Gila River but in many camps throughout the period.

“[People] really leaned into those things as a way of asserting their Japanessness,” Lau-Ozawa told AsAmNews.

Despite the quarrels, attempted forced assimilation, and shaming of their culture, the Issei and Nisei prevailed. After the war some families returned to Japan. Others traveled to the east coast where they could escape prejudice and find work. But those who stayed in the west and wanted to resettle in their hometowns faced extreme hardship and difficulty.

Families returned to lost land, property, and frozen assets. Most Santa Barbara residents were homeless. But the Japanese American community relied on each other. The Buddhist Church and temple transformed into temporary hostels until people could find a home. The Asakura Hotel and family remained in the area until its demolition in the 1960s.

People were pressured to relocate to different parts of the city. Staying in a dense community provided security against Asian hate but also put a target on community members’ backs. For some, they questioned if it was better to move elsewhere where they wouldn’t be singled out and would assimilate. They wouldn’t be labeled a “criminal” who went to prison.

The Congregational Church and Buddhist Church relocated to different parts of the city while the Nihonmachi shops were demolished. Additionally, post-war redevelopment focused on Spanish colonial aesthetics.

All that physically remains of the Nihonmachi are the artifacts dug up by archeologists like Lau-Ozawa and the preserved memories remembered by friends and families of the community. But the community bond remains as strong as ever.

Much of the Santa Barbara Japanese Americans dispersed to different parts of the county but continued to congregate and form a community at the Buddhist temples.

Currently, many Japanese American families meet and hold events at the Bethany Congregational Church and the Buddhist Church. Additionally, the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) remains prevalent in organizing events and provides cohesion within the community.

The cultural strengths, ties, and bonds within the Santa Barbara community have strengthened so much over the years that a new community center in Santa Maria is scheduled to open in Spring 2025. With groups like the JACL, historians and organizations like the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation working to uncover and preserve lost artifacts, and most of all, the Japanese American community persevering and continuing to pass down family stories, the Issei and Nisei’s turmoil, happiness, and strong connections will always be remembered and honored.

Santa Barbara’s Nihonmachi will never truly disappear.

AsAmNews is published by the non-profit, Asian American Media Inc.

We are supported through donations and such charitable organizations as the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. All donations are tax deductible and can be made here.