The region is finally showing clear signs of recovery from the multi-year pandemic but 2025 portends more serious headwinds against which regional governments and businesses will have to steer.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns may be a distant memory for many, their impact continued to shape recovery in Southeast Asia in 2024. According to the Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) September 2024 Outlook, Southeast Asia is expected to grow by 4.5 per cent in 2024 and 4.7 per cent in 2025, with the Philippines, Vietnam and Cambodia growing fastest. While Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines returned to their pre-pandemic (2019) rates of growth, the poorest members of ASEAN — Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar (CLM) — appear to have settled at a lower trend growth rate.

This overall positive performance for the region was due to resilient domestic and external demand, driving consumption, investment and exports. ADB expects sustained expansion in private consumption in the major Southeast Asian markets of Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia, due to a resurgence in retail spending on durable goods. Stable prices and increasing tourism also contributed to consumer confidence.

After a downturn, merchandise exports rebounded in 2024, driven by a recovery in demand from major economies (notably the US) for electronics and other manufactured goods. Driven by increasing global demand for Artificial Intelligence (AI) chips, the electronics and semiconductor industries have experienced a rebound, boosting overall manufacturing performance. This positive trend is expected to benefit high-tech exporters in the region.

Tourist arrivals have been increasing, with some countries like Vietnam exceeding pre-pandemic levels. The tourism sector is anticipated to fully recover from the pandemic-induced contraction in most countries soon, with the return of Chinese tourists in key markets like Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand.

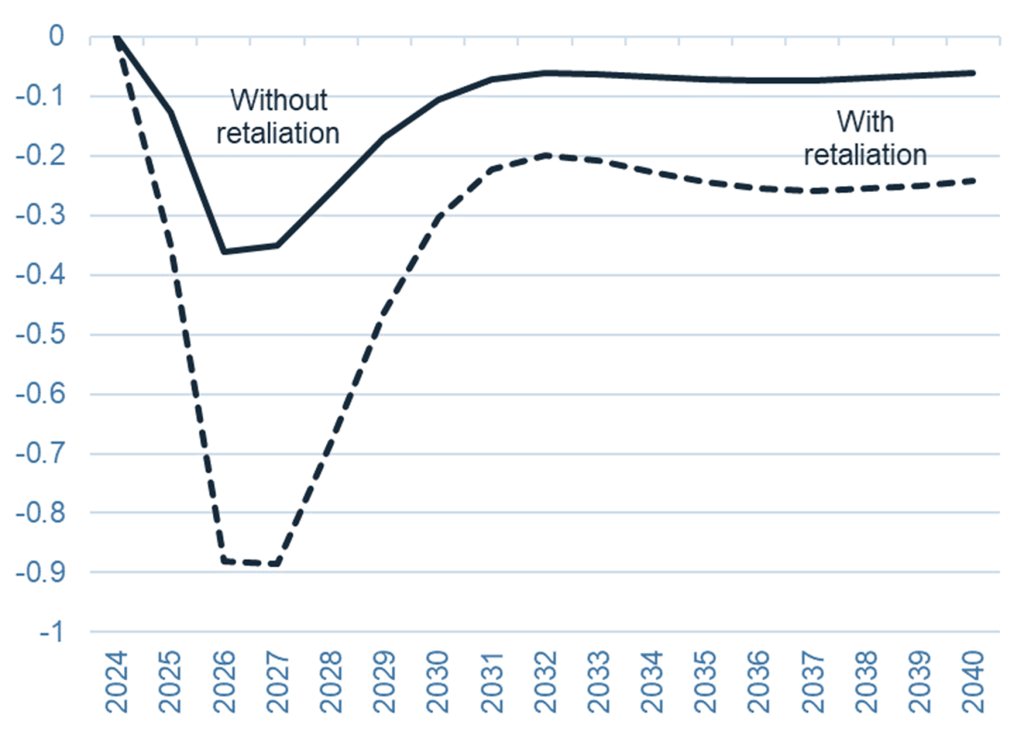

Despite the overall positive outlook, there has been an indubitable rise in risk and uncertainty affecting the regional and global economies. These include the consequences of the wars in the Middle East and Ukraine and further escalation in US-China tensions leading to increased protectionism. More than the kinetic wars, it is the US-China trade and technology war that is having the biggest indirect impact on Southeast Asia (Figures 1 and 2). Thus far, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia have managed to capitalise on this, attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) associated with supply chain reconfigurations in medium- to high-tech sectors, such as electronics and electrical machinery.

A further escalation in geopolitical tensions could reverse these gains by adversely affecting trade policies, security alignments, and regional stability. If incoming US president Donald J. Trump’s threats to raise new tariffs on China and other trading partners materialise, it could add to the bifurcation of supply chains. This would result in efficiency losses, raising costs to consumers and producers, and slower growth (Figure 1). Should an all-out trade war erupt (Figure 2), it could be disastrous for world trade and growth, derailing the region’s positive near-term outlook.

Although Southeast Asian countries can do much to mitigate the projected impacts of climate, technological, and demographic change, this is not true for the spillovers from the escalating US-China conflict.

Several other short- and long-term risks gathered momentum in 2024 that could impinge upon economic prospects in 2025 and beyond. While regional public debt levels have generally stabilised (except for Laos) following the blowout from pandemic-related spending, private debt, especially household debt, has grown considerably. For instance, household debt as a share of GDP is above 80 per cent in Malaysia and Thailand.

Further, Southeast Asia faces growing risks from more frequent and severe natural disasters and extreme weather events that could reduce GDP by up to a third through 2050. The poorer CLM countries will be disproportionately affected, given their relative lack of preparedness and greater reliance on climate-sensitive activities like agriculture and fisheries.

The rapid pace of technological transformation, particularly digitalisation and AI, will drive growth-enhancing productivity gains and generate good-paying jobs in the long run, but there will be adjustment costs in the short run, especially through the displacement of low-skilled workers. Estimates vary, but up to half of low-skilled jobs may be at risk. Reskilling the workforce and addressing uneven technological capabilities will be required to mitigate the short-run costs and the increase in inequalities, within and between countries.

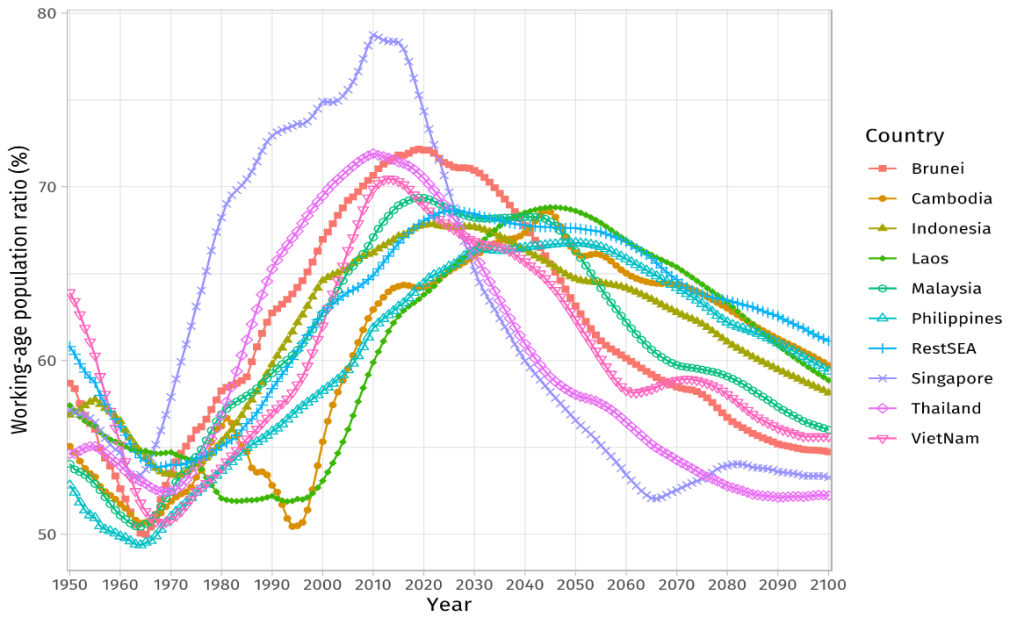

Meanwhile, Southeast Asian countries are ageing but not all at the same rate. Figure 3 shows that the working-age population in the CLM countries has yet to peak, while those in other ASEAN member states are declining. These divergent demographic trends present challenges and opportunities, posed by expanding and shrinking labour forces. Liberalising cross-border labour mobility would allow expanding labour forces, which happen to be in the poorer countries, to find employment in countries with shrinking labour forces, supporting growth in both. Labour-displacing technological change that will initially impact low-skilled workers increases the need for greater labour mobility. However, political sensitivities associated with liberalising such flows in a highly diverse region would first have to be overcome.

Although Southeast Asian countries can do much to mitigate the projected impacts of climate, technological, and demographic change, this is not true for the spillovers from the escalating US-China conflict. The conflict is also affecting the region’s green transition and technological progress. What the region’s governments and businesses can do is to continue to not pick sides and to avoid retaliatory actions, even if it becomes increasingly difficult to remain neutral.

Figure 1. Impact on Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) if US Tariffs (on World) Rise by 10 Percentage Points

Figure 2. Tit for Tat? Impact on US’ Real GDP (projected) if US Tariffs (on World) Rise by 10 Percentage Points

Figure 3. Ratios of Working-Age to Total Population (1950–2100), Southeast Asia

2025/6