I can’t remember precisely the first time I had boba; I only remember disliking it. I think I was too small to properly chew the tapioca pearls. Choking on them cemented my distaste for them. More than a decade later, I am now a boba fiend and always end up crawling back to my traditional order of classic black milk tea with pearls.

Like me, bubble tea originated from East Asia and was adopted by America. When I was 17 months old, a white family came to the Chinese province of Jiangjin and took me back to sunny California. I viewed my transracial family as normal (it was all I knew!), but as I grew up and moved to Colorado, it was clear I didn’t fit in. I am Chinese and I am American. But somewhere the lines blurred — I became too culturally white to be Asian and was too outwardly Asian to be white. I know I’m not alone in this feeling.

Food is often the first and most important cultural connection immigrants carry to their host land. Most kids with Asian parents are immersed in their native culture at home, whether that is making xiaolongbao with their dad, shopping for kimchi with their mother or wrapping onigiri with their siblings. These seemingly normal activities demonstrate the casual ways cultures comprise the immersive practices of generations. But for many Asian adoptees, there is no template to follow to learn these skills that perhaps all East Asians should know, like how to hold chopsticks properly.

Without an “Asian shaman” to teach basic dumpling recipes or to answer the internalized question of “how to be Asian?,” adoptees find other means to explore their own cultural identity. The nagging inquirer in me didn’t break through the surface until high school, when I met more adoptees and Asians. In an effort to explore my own sense of self, I turned to discovering new foods. I felt a responsibility to learn more about Asian foods, as I already loved cooking … and eating, of course. My entry point was — oddly enough — thanks to boba.

My discovery of boba occurred before it became an Instagramable, trendy new drink to try. What started in Asian enclaves in major cities quickly spread to chain restaurants across more suburban areas and birthed a new generation of Asian fusion that strayed further away from the traditional Taiwanese bubble tea. This “reinvention” of boba drinks in the United States serves as a good representation of the difficulties of assimilation of modern Asian Americans seeking to keep their Asian roots while also fitting in with American culture.

As Asian American youth consume a newly Americanized bubble tea, they begin to define their generation as one that is “upwardly mobile,” a term employed by The New Yorker writer, Jiayang Fan. The change in consumption of “Americanized boba,” (with boba flavors deviating from black tea with condensed milk and tapioca pearls to flavors like coffee or creme brulee) reflects how Asian American youth consume and adopt Americanized versions of Asian products, heritage or media as their own. This subculture plows its own path in distinction from their immigrant parents, establishing new means to acculturate.

Finding sanctuary in these products of consumption is applicable to the term “boba liberal” — one I personally had not heard of until I read Fan’s article. To boil it down, a boba liberal (a label popularized on X, because where else would such a name arise), is an Asian American who rallies around “acceptable” Asian trends when they are at peak popularity but who often ignores greater systemic, racial issues that are subtext in a broader cultural, political enterprise. In a deleted post, X user @diaspora_red called it “all sugar, no substance.”

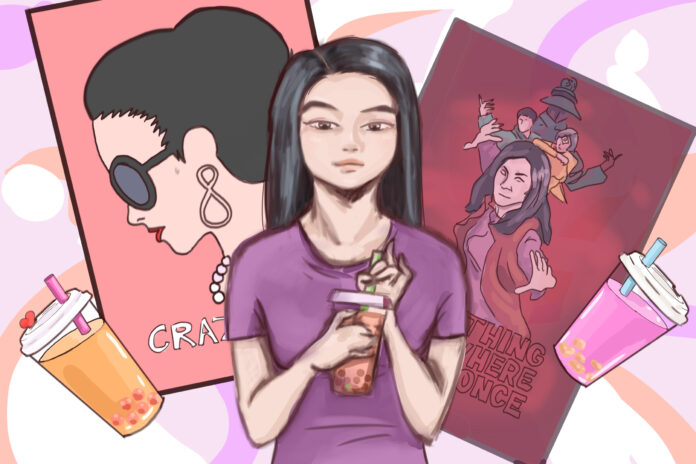

As Fan writes, “It’s the Asian who can’t stop talking about “Crazy Rich Asians” as a breakthrough in Asian representation, or who posts boba selfies as a way to prove her Asian bona fides while, elsewhere, seeking acceptance within white culture.” A boba liberal is someone who does performative acts to prove their Asian-ness while using these Asian foods and films as “cultural props.”

Now, there are two main parts to the definition of this label. “Boba” is the equivalent of these superficial props, while the latter term, “liberal” implies that these Asian Americans are not politically engaged, or that they are only engaged in surface level politics. The boba liberal issue made waves in pop culture last October when, in short, two French Canadian entrepreneurs appeared on Dragons’ Den, the Canadian version of Shark Tank. They pitched a healthier form of boba because, as they stated, “you’re never quite sure about its content.” Simu Liu, a Chinese-Canadian actor known best for his role as Marvel Studio’s “Shang Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings,” was a guest “dragon” on this episode and criticized their product as one of cultural appropriation.

While Liu made a valid argument that garnered lots of virality, it was, at the same time, accused of being boba liberalistic. Those who didn’t back him criticized him for using his platform to talk about something as seemingly insignificant as this product instead of greater issues facing the Asian American community.

Niche issues that have amassed similar attention like boba appropriation, the over-accentuation of the fox eye by white people or the qipao incident of 2018 are important. But, the disdain for defending these topics comes from the fact that they get more airtime than other issues of arguably larger reach and greater consequence. Criticism for the term boba liberal calls out Asian Americans who only appear vocal about superficial issues that increase their proximity to whiteness. In this sense, liberal is almost synonymous with “adjacency to whiteness.” This implies that in the same way many white people performatively value select people of Color issues, these boba liberals too ascribe themselves to white approval by backing seemingly palatable problems: problems that are valuable, but tamer and don’t ruffle as many white people’s feathers.

Out of fear of being labeled as a“boba liberal,” Asian Americans become discouraged from advocating for these more surface-level, introductory issues, further polarizing Asian Americans as a whole. Although activism for these smaller issues is a good starting point, it should not be the only thing we discuss. Political engagement is an ongoing responsibility of the Asian American community.

My central attachment to the boba liberal term comes from using boba as a superficial prop. For many Asian adoptees, these “props” act as our entry points into diving deeper into our cultures. To contend with Fan’s statement about how the boba liberal is “the Asian who can’t stop talking about ‘Crazy Rich Asians’,” I think that movie deserves all my love and more. The film introduced me to more works by its Asian actors and the relevant causes they support. In addition, I work at an Americanized boba chain — one that serves creme brulee flavored drinks. Working there introduced me to making boba from scratch, trying new drink flavors, enjoying hot pot with my coworkers and listening to an absurd amount of K-pop during my shifts. At first, I felt like a fraud participating in these experiences because I hadn’t grown up accustomed to them. Yet, food was the avenue I used to disrupt and dismantle my harbored feelings of inauthenticity.

Learning to make tteokbokki from my Korean friends, developing a taste and love for red bean or perusing the aisles of my local H Mart with my friends to find treats to stuff our faces with were all vehicles for my identity exploration. All of these cultural props may make me a temporary, transitional boba liberal, but they were necessary gateways to my identity exploration. Once that gateway is open, then a divestment from the “all sugar no substance” stereotype can begin, where more work is required to displace personal ignorance of greater struggles faced by other Asian communities.

The relationship between boba and representation matters only insofar as they both contribute to identity – how we find ourselves in these moments of cultural consumption. For those of us in marginalized communities, representation in film can further encapsulate the generational dichotomies between Asian immigrants and their children. Let’s take the film “Everything Everywhere All at Once:” an A24 production that opened the floodgates for Asian representation and proved to be a cinematic masterpiece in and of itself. To strip back all the multiverse jumping and perfectly sequenced fight scenes (if only I had Michelle Yeoh’s Kung Fu skills!), there is one key scene where Evelyn Wang (Michelle Yeoh), a Chinese American immigrant, reconciles with her estranged daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu) outside their family-owned laundromat.

It starts with Evelyn yelling at Joy, in typical tiger mom fashion, about Joy being fat, her not visiting when she says she will visit and getting a tattoo when she knows her mom is vehemently against them. Then the scene shifts in a flashing sequence of cutscenes, aka multiverse jumps. The scene is as confusing to explain as it is to watch, but the absurdism is the point — Evelyn and Joy’s interaction outside their laundromat is the only still event because it is their very relationship that holds together the universe. Evelyn states that even through all of their conflicts, she would not want to be anywhere else than with her daughter, cherishing the moments they spend together. Pretty straightforward, right?

The scene achieves two main things: One, it demonstrates the common generational gap between Asian immigrants and their first-generation offspring and two, it showcases how everyone seeks to be understood. These ideas are reflected throughout the whole film, but more specifically within the sub-universe of Joy and Evelyn’s tumultuous relationship. Actress Stephanie Hsu says, “Our generation and the younger generation is now exploring different types of strength and what it means to be strong when you’re compassionate.” Hsu isolates the younger generation in having this ability to learn these strengths independently of their parents. This separation reveals the new acknowledgement of — but not the new presence of — the generation of “upwardly mobile” Asian youth who deviate from their parents defining what it means to be Asian American in modern America.

Throughout all the multiverse jumps and boba runs, there is one common thread tying everything together: acceptance of one’s position in their culture, even amid the polarization of interpersonal identity. For Asian Americans who find it impossible to truly assimilate into America, there are barriers to being accepted into either culture. But we can use these means of consumption to find belonging. Culture does not have to define identity — identity can be independent of culture or intertwined with it.

To me, identity is fluid and can be an amalgamation of experiences. As Joy learns, in an almost-apocalyptic way, discovering one’s true self is a journey — it does not require all the answers at once. Feeling “in-between” or disjuncture with one’s culture is a catalyst to reveal one’s unconscious goals, traits and beliefs.

And without boba, movies or other cultural props, the door to deeper exploration of identity would be barred. These tools cannot do all the work for us to connect with our cultural identities, but they are good introductions. And just as Asian American activism can start with addressing more mainstream issues, it cannot end there.

MiC Columnist Karah Post can be reached at karahp@umich.edu.