The great-grandson of Wong Kim Ark — whose landmark 1898 Supreme Court case helped establish a birthright citizenship for all children of immigrants — blasted President Donald Trump’s new executive order seeking to revoke the long-standing right.

Norman Wong, 74, who’s based in Brentwood, California, called Trump’s directive “troubling” and said it is a move intended to fracture Americans. The executive order, entitled Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship, limits birthright citizenship to people who have at least one parent who is a United States citizen or a permanent resident.

“He’s feeding off the American mindset, and it’s not a healthy one,” Wong told NBC News. “We can’t build the country together and be against everybody. I think the best thing to do is for Americans to actually be embracing Americans.”

The Trump transition team did not respond to NBC News’ request for comment.

Despite having such a monumental role in establishing citizenship rules, Wong Kim Ark’s own son ended up being deported just over a decade later.

Norman Wong said that this shows that rights are always in flux, and need to be continuously advocated for.

“We’re going to get the world that we’re willing to fight for,” Wong said. “It starts in our hearts, what we believe … If we have good thoughts and work from that, we’ll get a better world. But it’s not going to be easy in this country.”

Trump’s executive order also stipulates that those born to parents who are in the country legally, but temporarily, will no longer be automatically guaranteed citizenship. This would include children born from people on student, work or tourist visas.

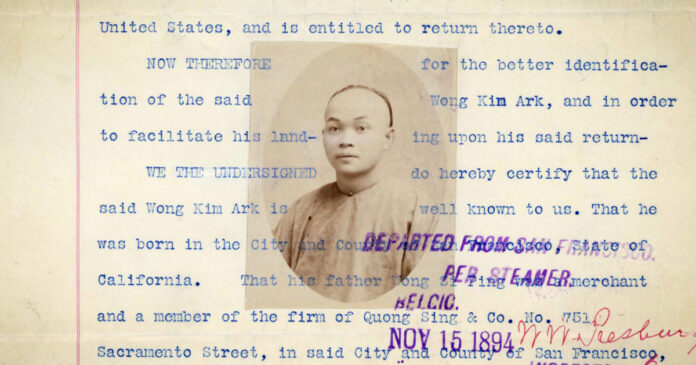

The directive comes well over a century after Norman Wong’s ancestor waged his legal fight. Wong Kim Ark, a San Francisco-born cook, had left the country to visit China and was barred from re-entering the U.S., arrested, and confined to the ship he had traveled in upon his return in 1895. Customs collector John H. Wise refused to recognize Wong’s status as an American and ordered him to be deported under the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited Chinese labor immigration.

Wong Kim Ark was the 21-year-old son of Chinese merchants who had entered the U.S. legally. Under the Exclusion Act, the parents were not permitted to get naturalized. It was an era of rampant anti-Chinese sentiment, with violent mobs often targeting Chinese businesses, and Wong’s parents eventually returned to their home country.

But the younger Wong fought to stay. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, mutual aid organizations that were often referred to as the “Six Companies,” stepped in to help and filed a writ of habeas corpus arguing he’d been unlawfully detained as a “native-born citizen under the Fourteenth Amendment.” The case made its way to the Supreme Court, whose justices sided with Wong in a 6-2 vote.

“The amendment, in clear words and in manifest intent, includes the children born within the territory of the United States of all other persons, of whatever race or color, domiciled within the United States,” the Supreme Court concluded.

Many decades later, Norman Wong himself spent his youth advocating for Asian American studies at Berkeley as well as community organizing in San Francisco. But it wasn’t until he was in his 50s, he said, that he found out about his ancestor’s impactful legacy. He recalled his father revealing that piece of history as they flipped through old belongings. And because he’s always felt like an outsider —both as an Asian American and as someone of mixed Chinese and Japanese descent — Norman Wong said the moment was important for him.

“It validated me,” he said of the discovery.

Wong said that the fight is far from over, however. And Wong Kim Ark’s story is perhaps a reminder of that. The cook’s eldest son, Wong Yoke Fun, was denied entry into the U.S. and detained at Angel Island years after the Supreme Court case, as immigration authorities held that he couldn’t prove his relation to Wong Kim Ark. In 1911, the China-born son was deported.

Progress, Norman Wong said, is “going to rely on the younger generation.”

“There’s only so much fight left in me,” Wong said. “Our hope is in our children. … the future always belongs to the children.”

Wong added: “I just hope they do the right thing.”

Trump’s executive action has drawn backlash from Asian American activists and lawmakers, including a legal challenge. The American Civil Liberties Union, with several other civil rights organizations including the Asian Law Caucus, filed a lawsuit Monday night accusing the Trump administration of “flouting the Constitution’s dictates.” And a coalition of 19 Democratic attorneys general have also sued to block the order.

“This is a war on American families waged by a president with zero respect for our Constitution. We have sued, and I have every confidence we will win,” Connecticut Attorney General William Tong said.

The chairs of the Congressional Tri-Caucus, which includes the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, the Congressional Black Caucus and the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, condemned Trump’s executive order, accusing the president of violating the 14th Amendment and his oath to protect and defend the Constitution.

“Through the hard-fought legal battle of Wong Kim Ark v the United States in 1898, the Supreme Court upheld that birthright citizenship is a constitutionally protected right, and it is President Trump’s duty, as Commander in Chief of the free world, to uphold the law,” the chairs said in the statement.